The Thurston Revival - Somewhere There's An Angel

![]()

![]()

︎ ︎ Flickr

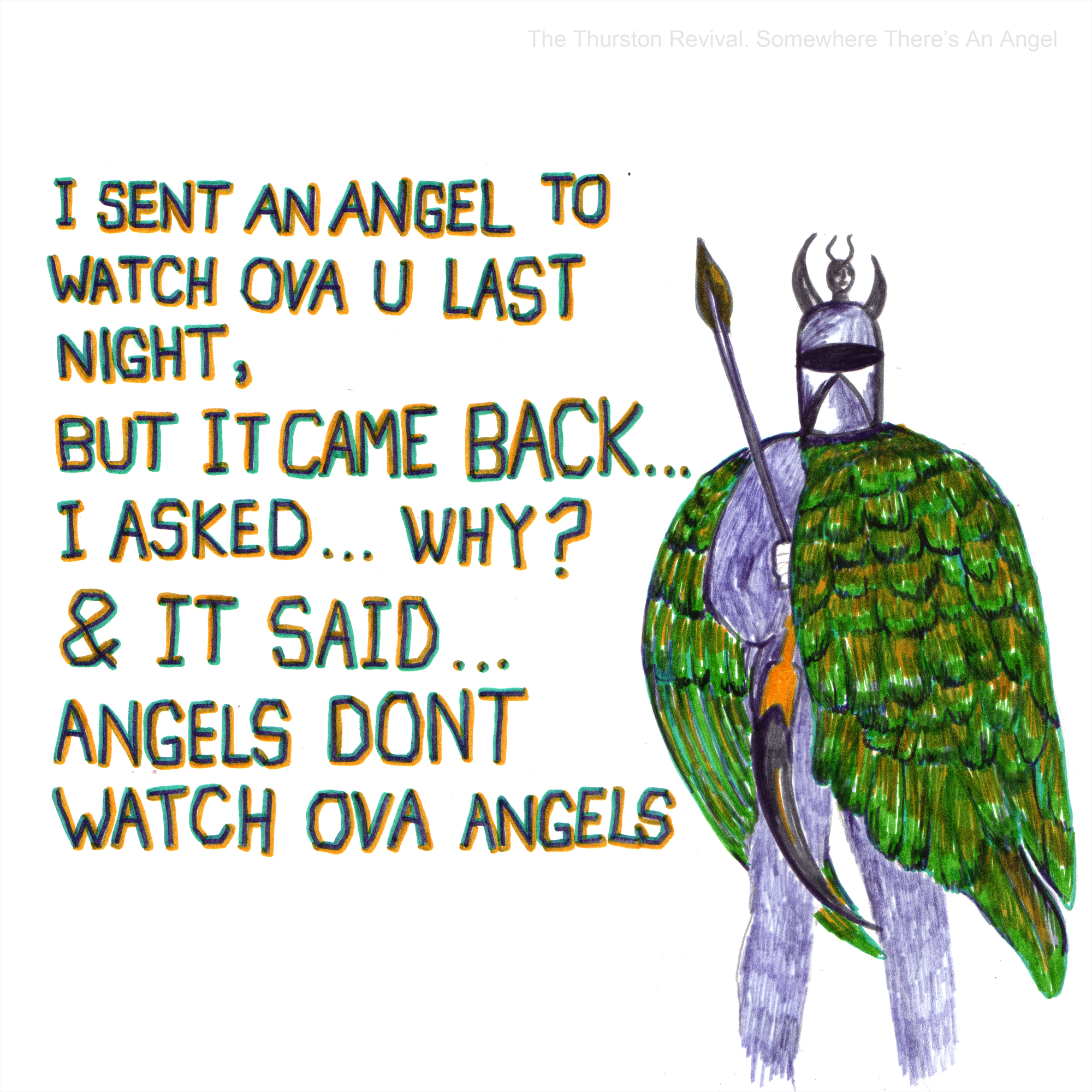

Illustration for the cover of the most expensive debut single ever

From The Sunday Times

August 12, 2007

Single combat

A new artist is issuing a bold challenge to an ailing record industry

Lisa Verrico's Times Review

How much is a song worth: £1.99 on CD; 79p as a download? How about £100 for a track from an artist you’ve never heard of? At a time when persuading people to part with any money at all for music increasingly resembles a lost cause, Dan O’Connell, aka the Thurston Revival, is set to release the most expensive debut single in the history of pop. The Maidstone-born, Vancouver-based one-man band is putting 100 vinyl copies of Somewhere There’s an Angel on sale for £100 each. Is he insane?

“How crazy I look probably depends on how many I’m left with,” laughs O’Connell, a wild-haired 24-year-old who describes his regular job as “slinging a sledgehammer”. “But I’m not bothered if some don’t sell. The hefty price tag is a statement on the value of music in general. Music’s value is subjective. How much you love a song has nothing to do with how much you paid for it. Somewhere There’s an Angel is on my page on MySpace and anyone can hear it for free. Does that mean the song has no value? Of course not. Yet that’s what we’re constantly told.” The Thurston Revival’s 100 singles will be exhibited later this month, for one night only, on the walls of the Sartorial gallery in London’s Notting Hill. To emphasise the art concept, 10 acclaimed young British artists, including Jasper Joffe, Sarah Doyle, Cathy Lomax, Edward Ward and Harry Pye, have each designed a sleeve – there will be 10 of each – inspired by the song. It’s a dramatic, cinematic ballad with powerful vocals that took O’Connell two years to complete and was inspired, he claims, by Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. A dozen copies have already been sold, but without prior knowledge of which artist created the purchased sleeve.

“The value of the product is not in the artwork, it’s in the concept,” insists James Barton, commercial director of Record of the Day, the London-based music company that set up the show. “We wanted to help Dan because Somewhere There’s an Angel is one of the most astonishing pieces of music we’ve ever come across. If any pop song can remind people that music is art, this is it.”

Barton discovered O’Connell by accident last autumn, at a gig in Manchester. “I was there to see another band,” recalls Barton, “when this 6½ft bloke wearing a medieval cloak strolled on stage. I half expected him to brandish a sword. Instead, he slung a strange guitar/key-board instrument over his shoulder, battered a broken drum machine and sang into an adapted 1930s RCA microphone. It was the most shambolic performance I’ve ever seen. But the man was mesmerising. He finished the set with Somewhere There’s an Angel and everyone was transfixed. It was one of those moments you never forget.”

Barton’s colleagues were equally impressed when the Thurston Revival played London the following month, and the company’s director, Paul Scaife, decided to set up a label solely to release Somewhere There’s an Angel. But when they took promo copies to radio stations, they were in for a shock.

“Everyone agreed the song was amazing,” says Barton. “But they told us it wasn’t a debut single. There is a certain way a new artist has to be presented to the public that has been adhered to for years. You put out one or two limited-edition releases, see how the taste-makers react, then hit them with your big tune. As a third single, apparently, Somewhere There’s an Angel would have been perfect. As a first, one head of programming told us, it was too good.”

Determined to prove old rules should not apply, Barton and O’Connell hatched the idea of an art show. “The plan is to generate enough attention that stations will play the track,” says Barton. “Our aim is to challenge the established means of selling music, which clearly aren’t working. Launching the Thurston Revival through a gallery came about because we’re tired of reading about music being worthless.”

Even if all 100 singles sell, however, O’Connell will turn only a small profit. As a promotional event, it may be inspired, but as a business model, it sucks. “The point is, we put a lot of effort into thinking of an original way to get this song heard,” says Barton. “Our challenge to the big record companies is that they should put as much

imagination into selling their artists. Music has been both free and paid for since the invention of radio. It’s on TV, on adverts, in movies. You could always listen to music for free, but if you wanted your own copy of a song, you had to pay for it. The internet has created a market where that is no longer true. But if you give people a reason to pay for a physical product, they will.”

A good example is Nine Inch Nails (NIN) and their current album, Year Zero – or, rather, the alternate-reality game that the band’s Trent Reznor devised to persuade fans to buy the CD. Printed on the disc and hidden within the expensive artwork (as well as on T-shirts) were cryptic clues to help his typically techno-savvy audience navigate their way through an otherworldly online labyrinth that will run for 18 months. NIN sites are buzzing with fans-turned-detective trading clues, and while piracy of Year Zero was rife, the bond Reznor created with players of all ages resulted in a boom in sales of his concert tickets and other merchandise. His record company was so impressed, it’s planning similar games for CDs by other artists.

Yet what works for NIN is unlikely to work for, say, a pop group or R&B artist. “Physical sales are in free fall,” concedes Barton, “and probably nothing can stop that. But to give up because conditions are tough is nonsense. The rest of the industry is booming: concerts are selling out, people pay £25 for a T-shirt. Record sales used to be the most profitable part of the business. They’re not any more, but that doesn’t mean they should disappear.”

As for O’Connell, he’s relishing recognition. “I recorded most of Somewhere There’s an Angel in my flat, in a soundproof fort made out of mattresses,” he says. “In Vancouver, they called me crazy. Over here, I’m a crazy artist.”

︎ ︎ Flickr

Illustration for the cover of the most expensive debut single ever

From The Sunday Times

Illustration for the cover of the most expensive debut single ever